<b>“I have not known anyone since Nietzsche</b> who shows so shockingly what a catastrophe it is to not believe in God." —<b>Robert Spaemann</b>

<b>"There are not many</b> who dare to speak of God as unabashedly as Esther Maria Magnis." —<b>Public Forum</b>

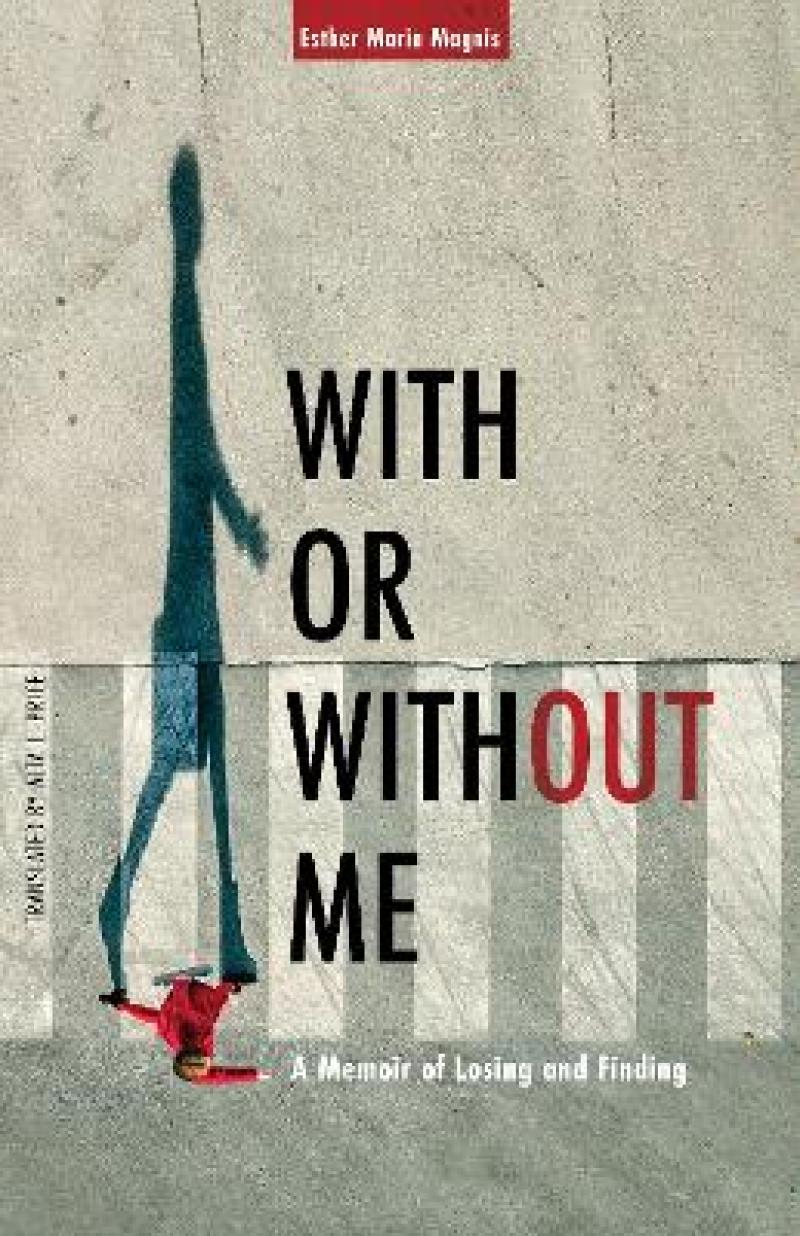

<em><strong>With or Without Me</strong></em><strong> is utterly necessary. </strong>Breathtakingly honest with unflinching rawness, this book<em> </em>is a must read for anyone who has ever pondered the meaning of life. —<strong>Lydia S. Dugdale, author of </strong><em><strong>The Lost Art of Dying: Reviving Forgotten Wisdom</strong></em>

<strong>Seldom have I read a Christian book that possessed such raw energy and passion</strong>. <em>With or Without Me</em> is an honest account of death, bereavement and grief which lays bare what it means to love and lose. —<strong>Inspire Magazine</strong>

<p><strong>Faith is like a piece of quartz</strong> that Magnis turns over in her palm, examining all its angles, the sharp edges and the shine. This lends <em>With or Without Me </em>a thoughtful and introspective quality, contemplative without being meandering... She deftly balances the transcendent and immanent as she recounts her walk towards God, yet never reduces her discussion of faith to abstractions. —<em><strong>Today's American Catholic</strong></em></p>

<p><strong>Esther Maria Magnis addresses traditional philosophy</strong> and religion head on in this unflinching memoir, which details her difficult sojourn away from the Christian faith and then back to it. Amid the spate of personal deconstruction narratives of the past few years, readers will appreciate this German author’s distinct perspective. <em>With or Without Me </em>is essential reading for anyone who has ever doubted God’s goodness in the midst of personal loss. —<em><strong>Christian Century</strong></em></p>

<p><strong>Magnis recounts</strong> with brutal honesty the depth of her loss. —<em><strong>War Cry Magazine</strong></em><strong>, UK</strong></p>

With or Without Me is a book for everyone – believer or unbeliever, Christian or atheist– who refuses to surrender to the idea that there are easy answers to the big questions in life.

Doubt about God’s goodness in the face of grief is natural. With or Without Me is one woman’s unsparing and eloquent memoir about the inadequacy of religion and philosophy to answer her emotional pain. Yet Esther Maria Magnis’s rejection of God is merely the beginning of a tortuous journey back to faith – one punctuated by personal losses retold with bluntness and immediacy.

Magnis knows believing in God is anything but easy. Because he allows people to suffer. Because he’s invisible. And silent.

“A must read for anyone who has ever pondered the meaning of life” – Lydia S. Dugdale, Author of The Lost Art of Dying

1

A thorn had scratched my leg. It was from a blackberry bush. I had spotted three red dots in a field of yellow grain, and immediately sent my bike’s silver handlebars, whose pink plastic grips gave me blisters because they were too small for my hands, swerving toward the side of the road. I had hopped off, letting my bike fall into the grass, and jumping over a little ditch. I’d heard a ripping noise – a thorn had torn a red gash into my leg, and a thin line of blood emerged. It wasn’t much, just enough to turn the cut bright red without flowing any farther.

But I didn’t care, because there they were: poppies. I wanted them. And now they were within reach. The wind was barely audible, the day and the fields were dozing in the sun, and the flowers’ delicate petals fluttered as I yanked their roots from the soil, squashed their stems between my hands and the handlebars, and rode home. One leaf was lost on the way, and another as I pulled up to the door. And then, in the vase that evening, the blossoms drooped and all the petals fell to the table. I tried this over and over as a kid. I’d always pluck another poppy, and was always a little disappointed when it wouldn’t bloom as bright or red in our kitchen.

Behind my closed eyes it was also red. From there, it was easy to sink into sleep. It was dark, too, but not dangerous; I knew this darkness, and found it comforting. Only when someone turned on the light, or I tried to sleep at the beach – then it was too bright. Otherwise, I liked the red behind my eyelids.

I had a calendar with nature photography where I discovered a red frog amid bright green leaves. I couldn’t believe it was real. I asked Mama, and she said it was, and that nature is full of amazing colors. She read me the calendar photo caption, and told me about the crabs in Africa whose red carapaces looked like caravans of little tanks crossing the road, back when she met my father.

I just can’t imagine large red things in nature. I can picture bloodbaths, when whales with white bellies swim up to the surface, but I don’t really call that nature. But maybe it is nature, I don’t know. It depends on who you are and how you view it.

-----

The first thing my little brother and I asked to do was pet the puppies. Our babysitter’s parents had a farm, and two weeks before, their dog had had a litter in their unused, green-tiled bathroom. Once we heard about it, we begged her every day for permission to see the newborn pups.

It stank in that bathroom, I bumped my head on the sink, all the little animals were crawling about, and I asked if I could take one home with me, but the babysitter disregarded my question. I was supposed to ask my mother or father first, or something like that.

Right next to the bathroom was a kitchen, and a bunch of old men sat on benches in the nook. There was a huge yellow ashtray on the table, like in a pub. The kitchen was filled with smoke. The men laughed as our babysitter walked us past the doorway. “Kids suit you,” one of the old grandpas said.

“Cut it, Papa,” the girl said, and I was astounded that the man with so few teeth left could be her father. I was four years old, and somehow I’d already grown fond of Westphalian farmers, despite being creeped out by their huge, chapped, red hands, which always crushed the fingers of anyone they greeted.

I had a tic; I couldn’t help clearing my throat whenever they spoke their Low German dialect, because to me their rolled r’s made them sound like their throats were blocked with phlegm.

“We’re just gonna visit the piglets, and then I’ll take the kids home,” our chubby babysitter said.

“Atta girl,” said one of the men on the bench.

The piglets were in a crate right behind the kitchen, in a dark little passageway. One wall of the crate was just a bunch of nailed-in planks, so at first you could only hear a muffled, high-pitched snorting and a light bumping sound against wood and a shuffling of straw on stone. The only light came from a red lamp in the crate, and you could see the little snouts poking out of the slits between the planks.

Johannes held my hand. The babysitter walked with us, right up close to the crate, and I peeked through one of the slits.

The red light made my eyes feel too hot to look, or maybe the piglets’ skin was too warm. In any case, it felt like a layer of something was coating my gaze, and nothing looked as real as I might have hoped. But my little-kid heart melted when I saw the pinkish-red creatures and how they excitedly wiggled, wagging their little wormlike tails.

I wanted to just pick them up and kiss their little wet snouts and pet them and rock them in my hand and lather them with pink shampoo and hug them close. I wanted to bring them home and put them in my baby-doll stroller so they’d never grow up.

“Can I have one, please?” I asked, exactly as I had before, with the puppies.

The babysitter laughed. “One of the piglets? Forget about it, girl.”

“But you have so many! You could give just one to me and Johannes. Right, Johannes? You wanna piglet too, don’t you?”

My little brother beamed and nodded. He always thought my ideas were good.

“You can’t need all of them, so you can give one away to us,” I said, and stuck my arm far into the crate, sleeve rolled up high, so I could pet as many as possible, all at the same time. Johannes pushed up next to me and thrust his arm along mine and patted around, pawing at the piglets I would have preferred to have to myself.

“But what are you gonna do with all of them?” I asked the babysitter.

“Well, they’ll be slaughtered,” she replied, and I felt my mouth form the “slaugh-” and the “-ter” as I tried to silently echo what she’d said; both syllables felt brutal but also grown-up. In any case, I sensed it was a word adults might be annoyed at being asked about. So I didn’t ask about it. I couldn’t have, anyway, because in the meantime Johannes had peed his pants and the babysitter had taken him to the bathroom. I wanted to stay with the piglets, so I was left all alone in the room, which as a kid gave me a strange sensation that was simultaneously exciting and fuzzy.

I can’t remember how long I stayed there, nor what I actually did during that time. But I remember the squeal.

The squeal sounded like someone had thrust a jaggedly sliced tin can into the mouth of a screaming woman. It rattled from the windpipe, through the nose, groaning, arising from the belly and suddenly growing shrill, reaching the highest, airiest pitch.

It pierced the hallway door, a towering, dark double door directly opposite the kitchen door. This was the door Johannes and the babysitter had vanished behind and, as my initial fright subsided, it was the door I had to go up to. I was afraid of annoying the adults. It was just like with the word “slaughter,” which I didn’t dare ask about, because it clearly wasn’t anything for a little kid, but this time I simply had to go and see.

As I stood on my tippy toes in order to reach the iron doorknob, I was more afraid of being caught than of seeing something scary. What kind of scary thing could I have dreamed up, anyway? I had no pictures. I wasn’t allowed to watch the news, hardly watched TV; I’d only been in this world a mere four years. But somehow even little kids can sniff it in the air when something’s up, and I just had to see for myself, even if only by peeping through the crack of the door.

As I bent forward on tiptoe and leaned against the door, it slowly, heavily, yet unstoppably swung wide open, crashing against the hallway wall. I stood in the doorframe and could smell blood steaming up from a kind of tub. Above it hung a sow, slashed open, and I wondered whether that was what had squealed. Her feet were bound by a noose hanging from a huge hook, and the men were pulling red stuff from her belly.

My memory is filled by a red haze, in some spots it’s as dark as the red behind my closed eyelids. The men wore aprons—they were towering figures. They were incredibly focused, and I just stood there and stared and kept staring, the way you stare at a math problem you’re supposed to be able to solve.

“Somebody get the little one outta here,” yelled one of the men in a blood-covered apron. He had a knife in his hand. I wasn’t afraid of him. For me, he was the epitome of a grown-up: a massive, serious, busy stranger.

The door was shut again, and through the slit I heard someone shout “Anni! Dammit again, Anni, keep an eye on the brats!”

Anni came back, holding Johannes’s hand, and drove us home. I wasn’t traumatized. I was fed meat as a child. Sausage and a slice of bread. Kinderwurst – children’s sausage – a fun-shaped baloney, at the butcher. I had no choice, no way of opting out. Just like my baptism. In both cases, nobody asked me. The first thing I drank was milk. Then came pureed vegetables and, with my first teeth, meat.

From the very beginning, I took part in it all.